How to Fundraise as a First-Time Founder

A Smart Generalist's Guide

Welcome to an insider-only edition! This is the ninth installment of Silicon Valley Startups, following:

The Basics (VC 101, Startups 101)

Finding a Career (How to Found a Silicon Valley Startup, How to Break Into Venture Capital, How to Join a Rocketship Startup, How to Choose)

Crushing Your Job (Getting Shit Done at Startup Speed, Company Building: My Playbook for Startup Ops, How to Play Politics Without Being a Total Loser)

This week, we’re talking about fundraising.

I have a lot of scar tissue from fundraising, all earned by raising $500,000 for my own startup, and $250 million for Astranis. We’ll focus on the former here, because I want this post to be targeted to Outsiders — first time founders, as I was, who know nothing about raising money in Silicon Valley but who want to start companies of their own.

When I set out to raise money for my startup (“Direct”), I had no idea what I was doing. The whole journey was an exercise in flying by the seat of my pants: taking meetings wherever I could get them, without much by the way of strategy. It’s a minor miracle that it eventually ended as I hoped it did — with a VC offering to give me $500,000 and kick off my startup dream — but I surprised even myself by turning the money down, and deciding to shut my company down instead.

The reason I shut the company down is because I went about fundraising the wrong way:

I focused too much energy on the presentation itself.

My pitch had the wrong focus.

I pitched the wrong people.

In the sections that follow, we’ll dive into each mistake in detail. It’ll be painful for me to relive, I’m sure, but instructive for you — and hopefully, it’ll prevent you from making the same mistakes that I made.

✨ Focus less on the presentation of your startup pitch, and more on the reality of the business it describes

I’m not going to lie. My idea for this startup was good.

The product was a way for telecom operators to combat fraud by replacing a third-party intermediary with a piece of software. Sounds boring, and it was. But it solved a massive problem (telcos lose tens of billions yearly on this problem), it had very clear good guys and bad guys (me; an inefficient, margin-robbing middleman), and the tech solution was simple (decreasing the risk that we’d flub that part of it).

The product was such a good idea, in fact, that it worked — someone else co-created the idea a year or so after I started my company, and they made it become an industry standard. (They didn’t become a billion-dollar startup… but they did make a big change to the industry landscape.)

I started the company by entering a pitch competition and recruiting an undergraduate engineer to build a prototype of the technology — I pitched my brains out, and we won.

I doubled down, entering us in another pitch competition where the top prize was $1 million. And we won… second place. Giving us a nice trophy, but zero cash. Big bummer — and then, literally the next morning, the dude who made the tech prototype decided that he’d rather intern at Facebook than build out the product with me that summer. Bigger bummer.

I took two lessons away from these early experiences — and both would come back to haunt me:

“People love my idea, so I must be onto something”

“There’s no way to get these engineers’ attention without paying them, so I’d better fundraise as fast as possible.”

And with that shaky foundation, I dove in. My pitch competition deck became my investor deck, and I set out to get as many meetings with top-tier venture capitalists as my fledgling network could support.

Over the next few months, my pitch improved significantly. I learned what investors cared about, and got comfortable with the subtler social rules that governed the process of finding connections to investors, making first email contact, getting them to agree to an in-person meeting, and making the pitch itself.

But my business was not making similar progress.

I found another “technical founder,” but also found it challenging to keep him engaged; I recruited one of my business school classmates to come with me on a trip to an industry conference (and he did great; his small talk opened the door to our first real customer relationship), but I never spent the time necessary to onboard him for real, or get him 100% bought into the idea of dedicating a lot of time to my idea.

Given that I was dedicating ~80% of my time to fundraising (with the remainder going to customer discovery), that meant the product itself was making zero progress. By the time that I found a financial backer who was sold on my dream, and on me as a leader, I simply hadn’t made enough progress with the technology, with building the team, or with actually validating the market opportunity.

Ultimately, walking away from that $500,000 was the right decision.

The best piece of advice I got while weighing the decision came from Yanda Erlich: “Don’t say yes when you’re willing to invest the money, say yes when you’re willing to invest the time.”

I wasn’t ready to spend 10 years of my life on that bet. So I said no, said yes to my role at Astranis, and lived to fight another day.

💫 The moral of this story — build the company first, and the pitch deck second.

I saw the pitch deck that Varda Space used to raise their seed round, and it was literally just a white background, and black, unformatted bullet points in size 36 font. And it was brilliant.

They sold what they needed to sell — the team and the dream — and didn’t waste their time doing anything more than that.

💭 Focus your seed-stage pitch on the team and the dream. Worry about the rest later.

Early investors don’t want you to say that you’ve figured everything out — they know that you haven’t, so don’t BS them. Early investors just want to believe that you are the right people to tackle the problems that lie ahead of you, and that if you can tackle them, the opportunity for this company is massive.

It’s that simple. They want to see that you have the right team in place, and that your ambitions are large enough (and the market big enough) to make this company into a massive success if everything works out.

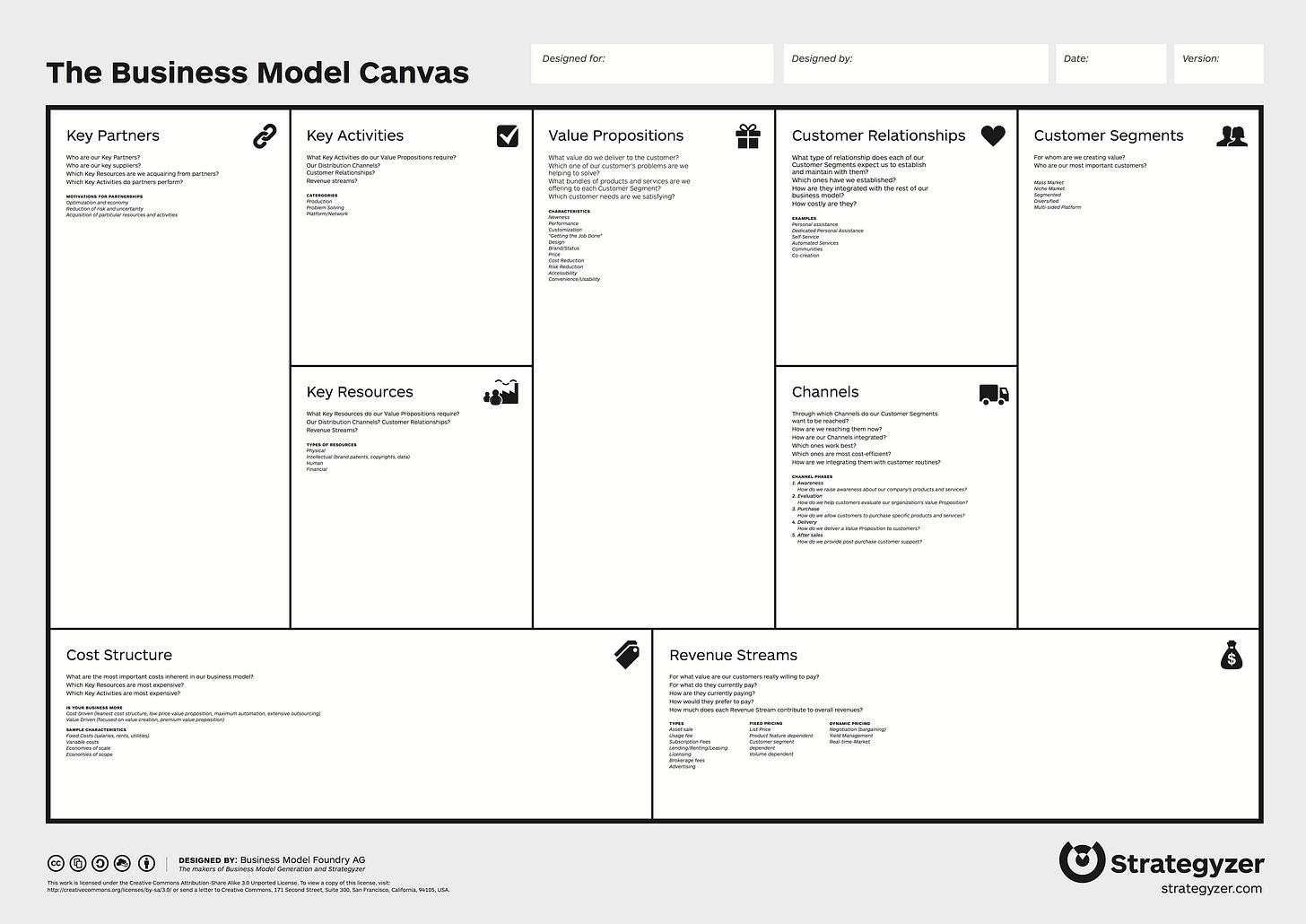

This was a revelation to me. And so freeing! I thought, naively, that investors would need to see a full “business plan” in order to invest in my idea. You know, one of these things, that maps out how the entire machine of the business is supposed to work:

Investors will, eventually, want you to be able to talk to all of the items on this sheet, and you should at least have a hypothesis for how these various pieces will come together — but nobody’s going to ask you to see any paperwork. Honestly, they might not even ask to see a pitch deck at all!

Investors all care about different things. Some care primarily about the ultimate size of the market; some care about having a deep customer insight; some care primarily about the personality, relationships, and skills of the founder. But they all want to see the team and the dream — so make sure you’ve got those two firmly in place before worrying about anything else.

A quick guide to dream-foretelling

You can make a compelling case that your startup will be massive in one of two ways: bottom-up, or top-down.

The bottom-up method looks at the individual unit economics and estimates how many of those units you might be able to sell someday. If your product is a phone that costs $300, everyone in America needs one to survive, and they replace it ~every year, that’s a massive market opportunity.

The top-down method looks at the overall amount of money that people are spending on something today, and extrapolates how much money they might spend on your thing in the future. For instance, if Americans currently spend $10 billion on cell phones today, and that number is growing rapidly over time, you’re looking at a big market.

Both of these methods can work, and you should probably just do both. But, when in doubt, focus on the bottom-up method. Investors hate the logic of “this is a $100 billion market, so if just capture 0.1%, we’ll make $100 million per year!” The simple reason why: they want to invest in market leaders who will win markets, not make a tiny, unsustainable dent in them.

😇 Raise from angel investors and accelerators, not VCs, to begin.

I pitched venture capitalists when I was trying to raise money, but I only learned later that I was violating an unwritten rule of Silicon Valley — it’s rare for big, institutional investors to put the absolute first check into a brand new company. It happens, of course, particularly for repeat founders.

But it is far, far more likely that you will get your first check from an angel or an accelerator than a name-brand VC.

Angel investors are individuals, often high-net-worth folks who were previously founders or investors before they hit it big.

You’ll also see groups acting together in the role of an angel investor these days — either as “syndicates” for an individual deal, or a “rolling fund” that is entrusted to an entrepreneur — which you can learn more about at AngelList.

These folks usually write relatively small checks, often just $100k or $50k, but do so well before any institutional investor would even take a meeting with you. They’re the best place to start: they are fine taking wild, lower-probability bets, they don’t need any particular return on their capital (as they are often investing personal funds), and they will generally prefer to sign a standard agreement like a SAFE rather than complicated fundraising paperwork that will cost you time and money.

Accelerators are early startup investing institutions that focus on actively helping their founders succeed through skill-building and introductions.

The best startup accelerator in the world is Y Combinator, an early investor in Airbnb, Stripe, Coinbase, DoorDash, Instacart, Brex, and dozens more name-brand, multi-billion-dollar startups. They run an intense, cohort-based bootcamp for their founders to teach them the ropes and, ultimately, introduce them to hundreds of top-tier investors at Demo Day.

The money that I was offered for my startup was actually through another prominent accelerator. (I won’t say who, to protect the innocent, but it wasn’t YC.)

YC’s money is expensive — $125k for 7% of your company — but it comes with serious name-brand appeal, and teaches invaluable lessons about the startup world, particularly to technical founders. Astranis has already had multiple alumni found companies that were eventually funded by Y Combinator… and I’m sure we’ll someday have even more! 👀

🃏 A parting tip: learn to play the game.

Like any complex social environment, the Silicon Valley startup world has a number of unwritten rules — things to do, or not to do, that can only be learned from the inside.

That is, ostensibly, why I started this newsletter. I knew none of the rules before getting here, and I figured that meant there was an opportunity to help founders outside Silicon Valley learn how to get fluent in our particular way of doing business.

To truly master the game, however, you’ll need to study it. Read the Silicon Valley Outsider backlog to start. And then you should also binge-watch Sam Altman’s course on how to start a startup, read all of the books, and follow the top Silicon Valley folks on Twitter.

Make a point of learning how to play the game. You’ll have to do so in order to maximize your chances of success — and this article is just a head start.