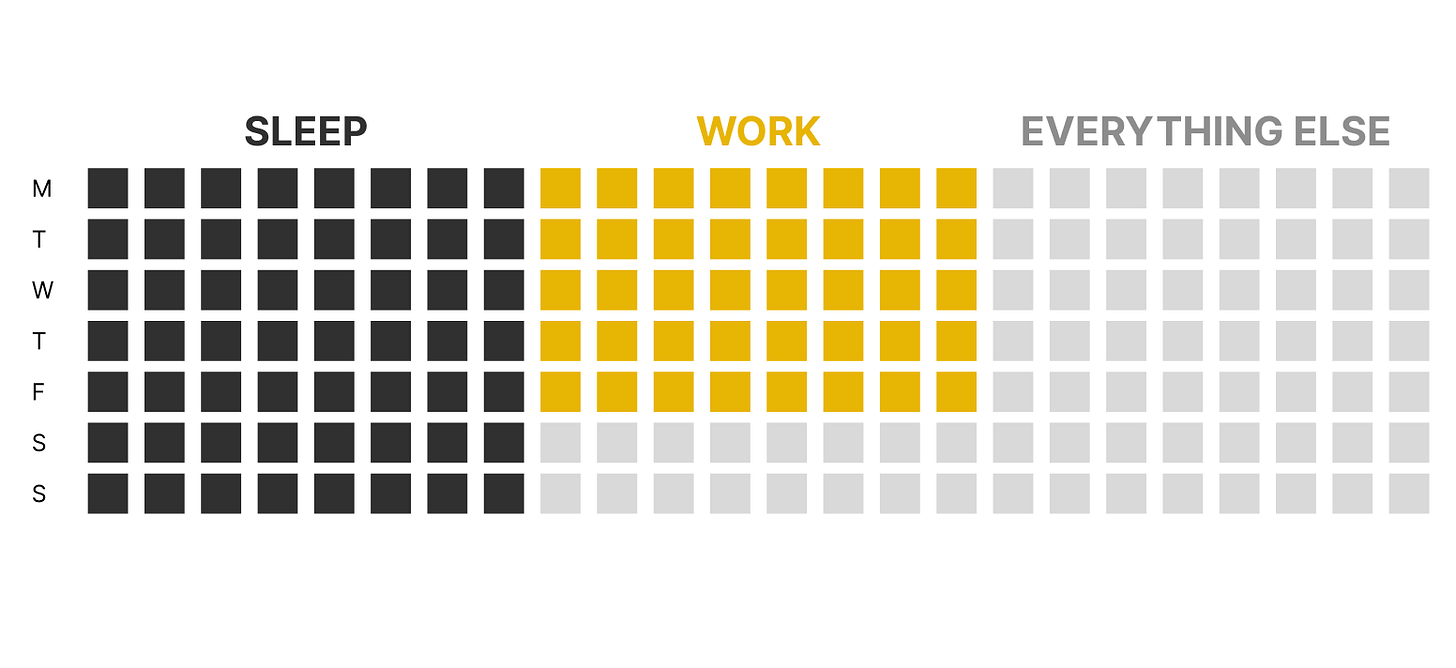

Choosing what to do for a living is one of the most important decisions of your life. Even if you strictly adhere to a clock-in, clock-out, 9-5 schedule, your work is still your life. You’re awake for only about 120 hours per week; you almost certainly spend a plurality of your time working.

Given that fact, one strategy is to separate work from life as much as possible. “Work-life avoidance” is an intuitively appealing strategy, but I’m not convinced it’s a winning one. It relies on a willingness to write off one third of your waking hours, and requires the willpower (or lack of will) to do a job that you don’t care about.

A much better, if more challenging, strategy is to try to love your work.

To care about the mission of your company. To master your craft. To believe that your hard work might lead to a better life for yourself, your co-workers, and the world around you. To find a job that makes you want to work hard.

Pursuing such a job is what led me away from consulting in Minnesota and towards startups in Silicon Valley. A common criticism of startup people is that they take themselves too seriously. But I’d much rather err on the side of caring too much than caring too little — and so I moved cities and careers, and ventured into the great unknown of the startup world.

When I got to California, I had no idea what I wanted to do, other than the vague “something to do with startups.”

My challenge was the challenge of any job seeker: it’s hard to know what jobs will really be like before you try them.

“Startups” was a fine hypothesis, but there are many different jobs in the startup world. You can start a company of your own. You can join a company with 10 people, or 100 people, or 1,000 people. You can try to join a VC firm, and invest in startups.

Those three jobs — founder, operator, investor — are very, very different from each other. They have fundamentally different risks; you’ll do fundamentally different tasks; you’ll be rewarded for good work in fundamentally different ways.

I’ve been lucky enough to try all three jobs over the last five years, so I have at least a taste of what life is like in them. I founded a company for which I raised $500k of venture funding; I was a VC Associate at two different venture firms; and I’m now the Chief of Staff at Astranis, a Series C startup that I’ve helped grow from 50 to 300 employees.

I’m in the middle of writing a series…

… and my pieces to date have covered the basics. They can give you a good overview of what it’s like to be an investor, a founder, and an operator at a startup:

We’re just about to graduate to the 301 level — but not before a quick interlude to help you choose which of these paths might be best for you.

Here’s how to know what’s right for you in the startup world.

👩🏽💼 Ask yourself “who,” not “what”

Don’t ask yourself what job you want, ask who — specifically — you want to be. Meet people in the actual roles you’re considering, and get to know them.

Ask them everything you can think to ask. What are the repetitive parts of the job? When they daydream about work on the weekend, what are they thinking about? What percentage of their job is in deep work, versus in meetings?

Beyond the specific questions, though, you should ask yourself whether you want to be that person. Would you consider your life well-lived if you swapped places with them tomorrow? Do they have skills that you want, friends that you want, opportunities that you want, possible futures that you want? If so, take a step in their direction.

The best people to choose for this exercise are people to whom you can draw a straight line. So, please, don’t choose Elon Musk, Barack Obama, or Oprah. Nobody knows how to become the next Oprah — not even Oprah.

Find someone who is about 5-7 years “ahead” of you on the same path; ideally, their last gig is similar to what you’re doing today.

Someone closer to your age has a chance of giving you helpful advice because they just made it through the world you’re now entering. A corollary to this role is that you absolutely should not take career advice from people an entire generation (15+ years) older than you. The world is changing too quickly for their personal experience to be relevant. And, again, they’re too far away to be able to draw a straight line from you to them.

The goal is not to map out your entire 40+ year career, but to figure out which direction you should step in next. The answer: whichever one gets you a little closer to a specific person of your choice.

🃏 What bet are you making?

Another tool to help you evaluate whether to move towards being a founder, investor, or operator is to be explicit about what specific bets you’re deciding among.

Be as detailed as possible. What results are you looking to achieve? On what timeline? What sorts of sacrifices to you think you’ll have to make? What other costs — comforts rejected, opportunities foregone — will you incur?

Through this process of defining your bet, you’ll learn a lot about your preferences. What do you want most in this next phase of your career: money, skills, a reputation, relationships, impact, something else?

Becoming a VC associate might be an awesome job for cultivating relationships, but if you don’t have carry, then it won’t be a way to build significant wealth. Maybe that matters to you, but maybe it doesn’t. Being a founder makes sense if you care less about having $$ today and care more about the potential of making $$$$$ tomorrow.

Be explicit about your bet — because then you can be honest later on about whether things are actually working out.

If you joined venture capital to network your brains out but they have you locked in the office writing deal memos all day long — the bet didn’t work. If you founded a company and you’re now feeling the pain of not having a stable salary — that’s what success looks like, as long as the dream is still alive.

When I started my company, I gave myself an explicit goal — I wanted to make $100,000 of revenue in my first year. I am, perhaps surprisingly, relatively risk-averse, and that (minus startup costs) was my minimum for sustainable/stress-free living in San Francisco. When I got to the end of that year, I didn’t hit my goal. I was tantalizingly close, and I had achieved other goals like raising money, but I had to have an honest conversation with myself as a result of missing the metric — and ultimately decided to make my next step in the direction of being a startup operator rather than a founder.

Define your bet clearly. It’ll be harder to fudge the numbers later if you do.

💱 How to choose between founder, investor, and operator

Alright, so with all of that framework out of the way: how do you actually make the decision between the three startup careers?

My best advice here is to assume that markets are rational. If you want to make more money, you’ll have to take on more risk. People occasionally make lots of money by getting lucky, but you can’t bet your career on luck. That means that the core question is simple: how much risk are you willing to take?

Here’s a ridiculously oversimplified risk/reward profile for each the three careers. (Assuming, importantly, that the VC role does not have carry — a good assumption for an entry-level role.)

There’s not much that can go terribly wrong as an investor, at least in the short term. The average fund has a 10-year lifetime, and a majority of the jobs in VC are at larger funds that have raised multiple successful funds already and will continue to do so in the future.

Your upside lies in the connections that you can make. Promotions from within into the big-money, carry-holding roles are relatively rare. Being a VC associate is a great way to learn a ton about the startup world, and search for the right company to start/join afterwards — it’s a long-term bet, and you shouldn’t join a VC firm hoping to make a quick buck.

In contrast, there’s a lot that can go terribly wrong as a founder. In fact, everything will go terribly wrong every day — but if you can keep the dream alive long enough, it might just come true. If you’re a truly successful founder, you can become a billionaire in a single generation.

But because the market is rational, being a founder requires taking a big career risk. The median outcome is zero return on your founding shares, and your reward is years of taking a low salary for your trouble. Zero return is also the 75th percentile outcome and 82.5th percentile outcome… at every stage of a startup’s life, there is roughly a 50% chance that it makes it to its next round of funding, at least through the first few rounds (pre-seed, seed, Series A).

It’s not a career move for the faint of heart. It’s also a long-term commitment; you should assume that if you take VC money, you’ll spend the next ten years trying to make this company a massive success.

I’m biased here, but being an operator offers a healthy balance of risk and reward. Your upside is millions of dollars, not billions of dollars, but you get to skip out on a lot of risk as a result.

When you join, your base salary will be pretty close to normal (tech) market rates. Your company’s runway will be longer, and your paycheck will be more secure. The odds of making some $$ on your equity will be far higher. You’ll still get some of the same freedom and responsibility that you expect from startup life, but you won’t go broke if the company fails.

As a result, most people that work in the startup world are operators, not founders.

This is obvious, if you actually think about it — there’s only ever one or two founders at each startup, and successful startups grow to be large companies with hundreds or thousands of employees. But you’d be surprised how few people think about joining a startup as a Plan A when coming to Silicon Valley. I certainly didn’t, and figured that starting my own company was the only way to get the autonomy and upside that I craved.

It was only after failing to be a founder that I realized there was another path. But you don’t have to make the same mistake.

There are great reasons to be a founder, of course, that have nothing to do with money. Similar stories can be told for investors, and for operators — you should make your decision based less on my advice, and more on what the direction in which you want to head: towards a specific person that you want to emulate, or at least while taking the best, most-informed bet that you can.

If you’ve made it this far, consider subscribing. I will release the rest of this series over the coming months, and most of those pieces will focus on how to crush a job at a startup — whether as a founder or an operator — once you’re there.

And if you’re already a subscriber, you know how to reach me! Let me know how I can help you make your decision — office hours are a free perk, and I’m happy to connect.

Thanks for reading Silicon Valley Outsider! Here are a few past editions that you might like if you enjoyed this one:

If you want to join 700+ folks in getting an email from me each Monday, I’ll help you understand Silicon Valley using normal-human words.