How Silicon Valley makes billionaires

Venture Capital 101 (MBA 80/20: Silicon Valley Startups)

Modern-day Silicon Valley is the singular best time and place to start a company in the history of the world.

Silicon Valley venture capitalists invest $60 billion per year into startups — that’s $25 million dollars invested per working hour. Since 2006, 50% percent of all billion-dollar startups, and 77% of all $10 billion+ startups, have been founded in Silicon Valley. And as a result, Silicon Valley has the most billionaires per capita in the world.

The best way to understand how, and why, Silicon Valley has become so successful at producing billionaires is to follow the money: to understand who venture capitalists are, what makes them tick, and how they decide which startups are worthy of investment.

That’s the goal of this post, the second installment of MBA 80/20: Silicon Valley Startups — Venture Capital 101.

Venture Capital 101

Some of the most important investment activity in Silicon Valley — and, therefore, the world — takes place on an unassuming suburban street in Menlo Park, California: Sand Hill Road.

Doesn’t look like much, but the buildings across the way belong to Lightspeed Venture Partners and Accel Partners. Combined, they have invested over $40 billion into startups like Facebook, Slack, Dropbox, Spotify, Etsy, Snapchat, Nest, GrubHub, Calm, and Zola. And that’s just two firms from a very long list of Sand Hill Road tenants.

$40 billion is a lot of money, and although the General Partners (GPs) that run these funds are doing just fine for themselves, they aren’t nearly rich enough to pony up tens of billions of dollars to invest in startups.

What that means is that VCs also have to raise money — and they do so from their investors: “Limited Partners.”

LPs are usually institutional money managers like pension funds, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds. Because they’re the ultimate source of money that makes the startup wheel turn, understanding what LPs want is key to understanding Silicon Valley as a whole.

⭐ To teach you more about Venture Capitalists and their LPs as efficiently as possible, I’ve put together three resources:

A video explaining the lifecycle of a normal VC fund, starting with raising money from LPs

A detailed post covering the math behind VC-led fundraising rounds: pre- and post-money valuations, dilution, pro rata rights, and more

An Excel workbook to give practical examples that test your knowledge of VC math

Without further ado, here’s Venture Capital 101 in 20 minutes or less:

Top-tier VCs want to deliver a 3x return to their LPs over the 10-year lifecycle of a fund. That’s about a 12% compounding return each year.

That’s not impossible, but it is high, particularly when dealing with the high-variability, high-risk world of early-stage startups. Of all startups that receive venture funding — which is already a hugely filtered set! — more than half fail.

To compensate, venture capital investors need to find big winners. As Bill Gurley, VC at Benchmark and early investor in Uber, said:

“Venture capital is not even a home-run business. It’s a grand-slam business.”

To understand this dynamic better, let’s start with the basics:

And before you continue to the written lessons below…

👉 Download this workbook to follow along.

VC Math Lesson One: “2 and 20”

VC funds earn money in two ways: they get a guaranteed “management fee” every year to pay their salaries and cover other expenses like office space, travel, Patagonia vests, etc; and they get a variable “carry,” meaning a share of the investment gains… that is, if their portfolio has gains at all.

A typical management fee is 2% per year, so for an $100 million fund, that’s $2 million per year. Not too shabby!

A typical carry percentage is 20%. It’s calculated as the percent of the total returns above the invested capital that is returned to the VCs themselves. Basically, they pay back their LPs first, then take 20% of any of the leftover profit.

For instance, if an $100 million fund returns:

$80 million: the partners get nothing. All of those exit proceeds head straight back to the LPs.

$120 million: the partners get $4 million, the LPs get $116 million.

These “2 and 20” terms are negotiable, and the best funds in the world can command higher numbers for both. The highest I’ve seen is 2.5 and 30.

VC Math Lesson Two: Pre- and Post-Money

Startup valuations often trip people up, and that’s because there are two ways to calculate a valuation — “pre-money,” and “post-money” — and people rarely tell you which one they’re talking about. They are very different from each other:

Pre-money means the intrinsic value of the startup’s business immediately before it receives VC cash.

Post-money means that intrinsic value of the startup plus the value of the cash it just received in the fundraising round

It’s really simple: a company that is worth $80 million raises $20 million of cash from VCs. The “pre-money” is $80M, the “post-money” is $100M.

In most cases, if someone quotes a company’s valuation, they mean post-money.

For example, Astranis is a $1.4 billion company; that’s the post-money of our most recent fundraising round. We raised $250 million to make it happen, so the investors said they think the value of our core business was $1.15 billion.

Perhaps confusingly, you can’t just divide 250/1150 to get the percent of the company that those investors own. Ownership is calculated using post-money valuations. So Astranis investors bought 250/1400 = ~18% of the company in that financing round.

If you’re ever wondering which is the correct valuation to use, just think of the investor’s cash. Before they invest, they own 0% and the company has a pre-money valuation. After they invest, they own [investment/post-money]% because the company has their money.

VC Math Lesson Three: Dilution and Pro Rata

When a VC invests in an early-stage company, they buy a certain percent of it — say, 20%. At the moment they do, assuming it’s the first fundraising round, the stake owned by the founders of the company goes from 100% to 80%. (Which makes sense; you can’t own more than 100% of the company!)

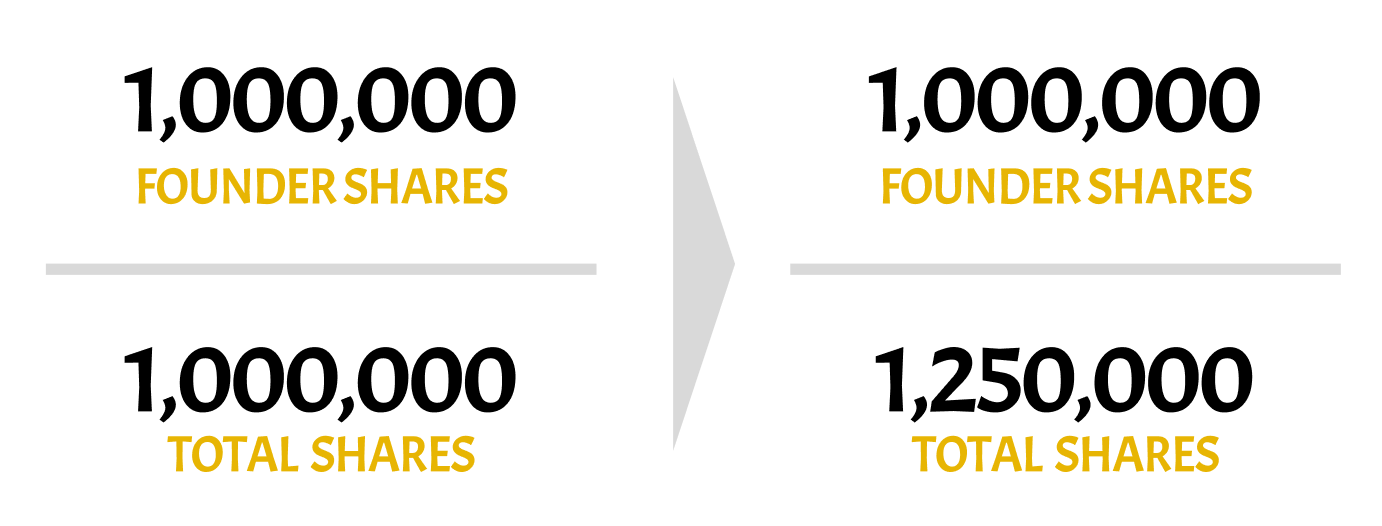

But the mechanism for that dilution of their stake is counter-intuitive. The founders don’t hand over some of their shares to the investors. Instead, the founders print new shares, and give new, not existing, shares to investors.

By doing so, the founders are diluting themselves. Before, their numerator of shares owned (say: 1,000,000) was the same as the denominator (1,000,000). But after they print new shares, the numerator stays the same while the denominator inflates.

Of course, the same sort of dilution can happen to investors. Say that a year passes and the startup wants to raise more money. To do so, they’ll print even more shares, say 1,250,000 more of them this time, and sell those to new investors. If the original investors don’t participate in the round, their stake will shrink from 20% to 10%! That’s bad news for the investors.

To protect against this, investors often ask for pro rata rights. This means that they have a contractually-protected right to maintain their percent holding of the company through subsequent fundraising rounds. In this case, the investor would need to buy a total of 250,000 shares from the new fundraising round to maintain their 20% stake.

Investors often want this right, but it’s a point of negotiation during fundraising. All else equal, founders would rather bring in new investors (and therefore new pools of money) into the fold. But if giving an early investor a pro-rata right is necessary to close the deal, then founders are usually willing to make it happen!

Alrighty, that does it for today! As always, thanks for reading, and I hope this course helps you out.

If you have any topics you’d like to understand better, or any feedback for today’s lecture, feel free to reach out to me directly at christian@pronouncedkyle.com.