Don't be afraid of working at a startup

A rebuttal to Evan Armstrong's "You Probably Shouldn't Work at a Startup"

When I was living in Minneapolis, I got an offer from a startup to build out their Midwest presence. I was in consulting at the time — a “prestige” career, at least in my mind at the time — so laughed off the offer. I couldn’t imagine why anyone in their right mind would work at a risky startup, especially one in a market with tons of competiton, obviously unsustainable VC subsidization, and approximately no product differentiation.

That startup was DoorDash. And, at their current $45 billion valuation, my equity would have been worth about $5 million. (Oops.)

I said no to the offer because I didn’t understand how startups worked, and I reduced the decision in my mind to “do I think this company is likely to succeed?” That’s a pretty bad way to think about startup life, but of course, I didn’t understand that at the time.

Evan Armstrong’s article on why startups are overrated advances a version of this argument, and therefore deserves to be debunked. Silicon Valley Outsiders (like those from my native Midwest) are too often barraged with pessimistic, alarmist takes on why startups are overrated, dangerous, or evil — so consider this an attempt to explain why startups aren’t always so scary when you rationally consider the risks and rewards of startup life.

1️⃣ Uncapped Upside

If I asked if you wanted to buy a $1 ticket for a raffle with 1,000 entries, you might say that the raffle is “risky.” After all, 999 times out of 1,000, you’ll lose your dollar and walk away with nothing. But if the grand prize for the winner was $1,000,000, you’d be nuts not to buy as many tickets as you could get your hands on. The conclusion is obvious: both the odds of success and the magnitude of success matter when rationally considering a bet.

Unfortunately, most folks don’t apply that kind of rational lens to evaluating the riskiness of joining a startup — they see a low probability of success, and head for the hills.

To his credit, Evan Armstrong considers both probability and magnitude in his assessment of the expected value of joining an early-stage startup. He finds a source that says 1% of all startups become unicorns (meaning, privately-owned companies that are worth more than $1 billion) and does some napkin math to calculate the expected value of working at an early-stage startup:

He then concludes that this, spread over four years, is not enough of an upside to justify the salary difference between Big Tech companies like Facebook/Google and startups.

But, even putting aside the fact that the alternative to a startup for most people is not Facebook or Google, there’s a bigger problem here — $1 billion is the minimum, not average, unicorn valuation!

Evan has committed a cardinal sin in evaluating startup odds: literally the entire point of the asset class is that the upside is uncapped.

The real math, according to the source Evan found, should look like this:

This might seem pedantic, but it’s important to internalize: the world’s biggest startup successes are really, really, unfathomably big.

At top-tier venture capital funds, about 90% of total returns come from the best startups, those that return >10x their initial VC investment. And the return for those companies doesn’t average 10x (as it would, via Evan’s logic). They average 64.3x.

It’s counter-intuitive to look at a 1% chance of success and think “that’s a high expected value.” But it’s true, and understanding why it’s true is important for anyone considering a career at a startup.

2️⃣ Intermediate Wins

Imagine, to continue the raffle analogy, that in addition to the grand $1,000,000 prize, I was also willing to award 9 additional $1,000 prizes. Such a fact should absolutely influence your willingness to pay for a ticket — and it’s important to remember that those intermediate wins can also have a substantial impact on the expected value of a bet, even if they’re much smaller than the grand prize.

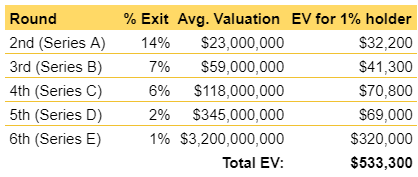

Unforunately, Evan also ignores the non-unicorns all together in his math. But many startups give paydays to their employees before they become unicorns; the evidence is in the very chart he highlights in his article. Check out the far right column. Those are all intermediate wins!

According to his own data, 14% of all “2nd round” (i.e., Series A) companies “exit” (meaning, sell to another company or go public). These companies are normally valued at around $23 million, so let’s simplify and use that as an estimate of exit valuation. If you own 1% of a company that’s worth $23 million, that’s a $230,000 payday — or a full $32,200 of expected value that Evan is straight-up ignoring… just from “2nd round” companies alone.

Here’s what a full expected value analysis would look like, using Evan’s data:

In total, this quick and dirty math suggests that Evan is underestimating the expected value of accepting a seed-stage offer by more than 5x.

The moral of the story is that even “failures” by venture capital standards can result in great financial outcomes for startup employees. You might not be a millionaire if your company is sold for less than $1 billion, but I certainly wouldn’t say no to a $230,000 bonus — and such bonuses shouldn’t be ignored when trying to assess the expected value of accepting a startup offer.

3️⃣ Alignment, Alignment, Alignment

Evan also moves beyond the financial aspects of startup life to claim that startup work is emotionally challenging — he says that the mission-driven stuff is BS, just ammo to make people work harder, and that you would get better experience working in Big Tech, where you can deploy products for tons of people.

Those criticisms fall flat for me. I know many folks who work in Big Tech, and while some of them love their jobs, most describe challenges that sound a lot like what I experienced while working in consulting: most notably, a lack of alignment. (I’ll explain.)

In his rebuttal to Evan’s piece, startup founder Nathan Baschez explains why startups offer a perfect environment for driven people like him who genuinely care about making a difference at their companies:

I still give way too much of a shit about whatever is right in front of me. I pour my whole self in… I’m like a firehose with no “off” switch—if I’m pointed in the wrong direction it can be dangerous, so the coping mechanism I’ve developed is to choose my projects with care. I can only work on things where it makes sense to pour my whole self into it. Like startups.

I can absolutely relate. I want to work extremely hard and would be absolutely miserable at a 9-5 job.

Case in point: at the end of a summer internship at a Fortune 100 company, I was given the superlative award for “Most Likely To Look Over Your Shoulder.” They were right. I was constantly peeking at my coworker’s computer screens to see what they were doing because it didn’t seem like anyone was actually working! As interns, we had maybe an hour of work to complete each day, and I couldn’t figure out what everyone else was doing for the rest of the eight hour work day. I was bored stiff, and lept at the opportunity to pursue consulting instead of an easy, low-burn job.

Startup life has proven even better than consulting for a number of reasons, chief among them the alignment I feel between my preferred working style and that of Astranis. If I’m going to work hard, I would want all of the following things to be true:

My company’s work actually matters for the world

My personal work actually matters for the success of the company

My personal work and my company’s work actually matters for my career advancement and my financial success

Astranis has absolutely lived up to all three, and so I have no trouble working extremely hard to make this company a success. Evan’s critique focuses on the mission-alignment aspect of the above, and, perhaps surprisingly, I have to agree — many startups probably don’t have exciting missions. But the best startups do!

Here’s some advice that’s way easier said than done: you should find, and join, companies like Astranis that inspire you to work hard.

4️⃣ Political Maneuvering

One of Evan’s final critiques of startup life is that startups are political, because the founders have power. I honestly find this criticism confusing — I wonder if he has experience working in big companies where many people have the authority to shut down your initiatives, rather than just one or a few — but I still think it merits answering.

In my experience, startups are remarkably less political than large companies — as they must be, given the incentives at play.

In a startup, two things are true: each individual owns a sizeable amount of equity (compared to a normal public company), and there is more potential success in the future than realized success in the present. As a result, each startup employee benefits more from growing the size of the future pie than from stealing more of today’s pie.

At a big company, the conditions are reversed: each individual owns a relatively small amount of equity, and there is more realized than potential success. In that world, selfish behavior is rewarded. You, as an individual, are unlikely to take the company down by doing what’s best for you and you’re less likely to personally gain by working yourself to the bone. So why would you? It’s rational to spend your time telling people about how great your work is instead.

The result looks something like this:

These incentives are real, and I’ve seen them play out throughout my career. So has Nathan — but apparently Evan hasn’t experienced something like this, with his reverence for working at big companies that have “scale.” To me, scale has a dark side: it can mean that your contributions don’t really matter.

Maybe that sounds great to you! But to me, being paid to complete tasks that don’t matter sounds like a special kind of hell — which is why I’ve found such a great home in the startup world.

In the end, navigating your career is a deeply personal choice — so the decision is up to you. But don’t say no to a startup just because you’re afraid that it will fail, or because you’ve heard that the mission-alignment stuff is BS.

On the financial front, just do some expected value math to determine whether a startup offer makes sense. (Just don’t underestimate the potential for a ridiculously huge success, or forget to include intermediate wins!)

And on the cultural front, do your best to find startups that come recommended by people you trust. It can be hard to sift through the noise — startups, if nothing else, are often great at playing up their own hype — but remind yourself that you’re looking for alignment, not hype, when finding a startup worthy of your time.

If you are startup-curious and aren’t already a subscriber, I’d recommend following along. And if you are a subscriber and want an inside scoop on a startup that you’re considering joining, definitely reach out. I hit the jackpot with Astranis, and I want to help all of you find jobs that make you excited to go to work every Monday.

Thanks for reading!

My name is Christian, I’m the Chief of Staff at Astranis, and I’m a native Midwesterner. If you enjoyed this piece and want to join 340 folks in getting an email from me every Monday, I’ll help you understand Silicon Valley using normal-human words.