Welcome, new subscribers! I’m Christian Keil, the Chief of Staff of Astranis, and this is my newsletter for startup-interested folks who live outside Silicon Valley. I usually write about stuff like how to find a business role at a startup and the best Silicon Valley books.

This week, in honor of a new book that features my writing (!), I’m instead going to write about my time as a startup founder — specifically, what led me to start a company.

Happy reading, and, as always, feel free to reach out!

🤓 I’ve always been in love with computers.

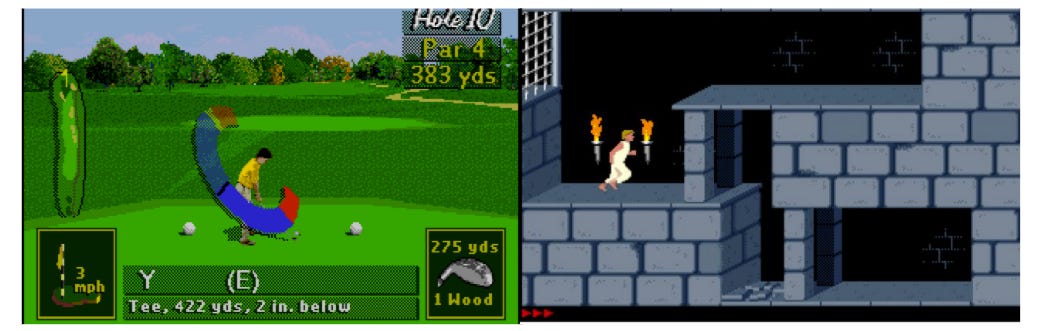

I remember sneaking downstairs at my aunt’s house in Michigan to play PGA Tour ‘96 on MS-DOS, and stealing extra seconds of Prince of Persia before my day care lady made me run to catch the elementary school bus.

I’ll never forget the day I first heard the dial-up modem say “oOoOoOopshhhkkkkkkrrrrPPPSSHHHRHHkakingkakingtshchchchHCHHCH” — which eventually led me to drill a hole through the ceiling to get an ethernet cable to my Xbox in the basement, convince my parents it was okay to buy things online, download Photoshop CS3 from LimeWire, “slice” custom website designs, and run my own phpBB instances. In fewer words, I have always been a nerd.

For a long time, however, I was the only nerd that I knew — which led to me become a nerd in denial. I hid my nerdiest interests from my friends in high school and college, and decided to pursued “normal” majors like Psychology and Economics in college. Over time, I further distanced myself from my computer/internet hobbies and got a nice, normal career as a management consultant, mostly focusing on telecommunications (think AT&T and Verizon).

Throughout the early years of my professional career, however, I came to two incredibly important realizations:

1) Businesspeople might own the present, but nerds own the future.

2) The future of the internet was coming fast.

Even in my dark night of the (nerdy) soul, I tried out new tech as I found it. When I came across a new kind of internet money in 2013, for instance, I gave it a try.

I honestly didn’t think much of it at the time. The “Bitcoin” stuff I found was pretty cool, and I enjoyed playing around with the sketchy, primitive tools that let me access it, but it was still just a novelty.

But in 2015, I learned about Ethereum, a new kind of digital money that also granted you access to a globally-run, infinitely-extensible computer. I had never heard of anything remotely like it — it was like its creator, Vitalik Buterin, was an alien dropped on Earth to show us galaxy-brain tech — and I was so excited by its possibilities that I fully reverted to my true, nerdy self.

I quickly became convinced that Ethereum could do for the internet what internet did for computers. And I knew that I wanted to stay close as the newly-minted “blockchain” ecosystem continued to mature.

From 2015-2017, I transitioned out of my career in consulting and into the world of entrepreneurship. As I’ve written about before, my risk-aversion led me to apply to business school and only move to Silicon Valley once I had a safety net secured.

Once I got to Berkeley, I knew that I couldn’t go it alone: if I wanted to start a real company, I had to find my people.

Luckily, living in Silicon Valley meant that I didn’t have to look far — it turns out that Berkeley had the world’s best blockchain club. Go figure!

After plugging into the group, I was introduced to the Blockchain Research Institute (BRI), a think tank founded by Don Tapscott — who I immediately recognized as the guy who wrote the book on blockchain. Miraculously, he needed someone who knew both telecommunications and blockchain, so he brought me onto his staff to write a “Big Idea” white paper exploring the impact of blockchain on telecom.

That paper became Distributed Connectivity: The Blockchain-enabled Future of Telecommunications, and led me to an idea that I thought to be compelling enough to launch a startup to pursue! If you’re interested, you can read more about that story here:

Over the following years, I continued working with the BRI as a way to guide my own research into this new technology, and I eventually wrote five whitepapers for the group, two of which are now being turned into a book!

Here’s a quick taste of what those two papers are about:

Saving the Web

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

The year is 2040. As David Foster Wallace’s young fish knew nothing of water, so, too, do our youngsters know nothing of connectivity:

it makes no sense for them to consider a world in which they—or anybody, or any device—isn’t always freely, openly connected to the Web. Every person on the planet will have open access to the Web; connectivity is a right as fiercely protected as life and liberty.“Connectivity” also holds a new connotation: it implies not only a point-connection to the current state of the Internet, but a clear view into the past. All Web pages are traceable back in time: consumers have perfect information on how headlines, prices, and corporate missions have changed. Accordingly, censorship is a political ill of an older age: the full history of the next-gen Web is instantly attainable, a reality no government nor corporation can sidestep.

Standardized and Decentralized

A modern blockchain stack should generalize beyond Bitcoin. In 2014,

it may have seemed like a great majority of blockchain transactions

would always run through the Bitcoin blockchain—it represented over

90 percent of the total market capitalization of all cryptocurrencies

combined at the time. As of 2018, however, that same number is

less than 35 percent. The emergence of Ethereum (~20%), Ripple

(~10%), and numerous altcoins gives credence to the belief that the

future of blockchain technology won’t be dominated by any single

blockchain.

Rekindling my nerdiness by diving deep into the blockchain world taught me a lot, but no lesson was more important than this:

If you want to live at the forefront of new technology, you need to find compatriots that can catalyze your enthusiasm.

🌕 Shoot for the stars, and maybe you’ll land on the moon. The San Francisco Bay Area is magical. Even though my first attempt at starting a company ended in failure, I was surrounded by people who were also trying to change the world, and landed on my feet. Physical (or social) proximity to inspiring people is crucial if you want to make a difference.

👭 Nobody has what it takes to change the world alone. You need people to sustain you when you’re exhausted, to guide you when you don’t know what to do, and to join you when you’re onto something and need more firepower. Finding peers who can motivate and help you is key; inspirational people are ever-present in Silicon Valley, but you can also find them through organizations like the BRI. Remember: you’re looking for people who test your beliefs and motivate you to act.

📝 It’s easy to be an armchair pundit. It’s very easy to overestimate your own skills if you never put them to the test. I thought I was an “ideas guy” in the making before I found a group of people that could really challenge my thinking. Now that I write short-form stuff weekly and long-form stuff with the BRI, however, I am constantly forced to reconcile with how little I know — and to do my best to fill my knowledge gaps whenever I discover them.

In short, the best way to successfully pursue what you love is to find people who can help you along the way.

Writing for the Blockchain Research Institute has massively improved my understanding of the future of the internet, and I’m incredibly grateful that they’re turning my essays into a book that can reach even more people.

If you’re still looking for your people, let me know — I’m happy to be the beginning of your Silicon Valley network, and to point you in the direction of other smart people who are just as obsessed about [the internet, gene editing, green tech, nuclear energy, …] as you are.

Thanks for reading Silicon Valley Outsider! I’m Christian, the Chief of Staff of Astranis, and I write this newsletter for folks who are interested in startups but live outside of the SF Bay Area.

If you want to join 500+ folks in getting an email from me each Monday, I’ll help you understand Silicon Valley using normal-human words.

Here are a few past editions that you might like if you enjoyed this one: