Welcome to Silicon Valley Outsider, a newsletter for aspiring entrepreneuers and investors who live outside the SF Bay Area.

🍎 Quick Bite of the Week: Big week for your author — I turned 30 and Astranis raised $250 million at a $1.4 billion valuation. (Pretty solid excuses for missing Outsider last week, if you ask me.)

I moved to Silicon Valley with big dreams.

I wanted to, in no particular order: found a startup; be my own boss; work with people who knew what Snapchat was; become rich and famous; befriend Elon Musk; learn what “Venture Capital” meant; understand the humor of Silicon Valley; and make the world a better place.

In fewer words, I wanted to be a part of Silicon Valley, even though I had no idea what it was really about.

One of the many things I didn’t yet know: there are many ways to start a company. Every year in America, three million businesses are created and just 20,000 get knighted as “startups” by Silicon Valley-model investors.

The companies that get such investments fall into a relatively tight mold — and understanding the Silicon Valley startup model is key to understanding if you really want to start a “startup,” or if you’d be just as happy founding a different kind of business.

⚾ The Silicon Valley startup model

In Silicon Valley, Venture Capitalists (VCs) fund startups. They raise money from Limited Partners (e.g., college endowments, pension funds) and earn a return by putting their money into fast-growing startups. On its face, this seems like an accuracy challenge — implying that the world’s best VCs are those that successfully identify good startups (and turn down bad ones) at the highest rate. But it’s not.

Great VCs aren’t any better than good VCs at finding startups that will reliably return money on each investment. In fact, the best VCs are worse than average VCs at not losing money.

Check out the gray bar on the bottom of that chart — deals that return <1x (lose money). >5x funds had more misses than 2-3x funds.

What makes a great VC great, then? When they win, they win big.

Per Benedict Evans (former investor at Andreessen Horowitz):

If you're a portfolio manager in a conventional public equities fund and you invest in a bunch of stocks that go down (or underperform the index), you could well lose your job, because your other investments can't make up for that loss. And if a public company went to zero, that would meant that a lot of people had screwed up really badly - public companies aren't ever supposed to go to zero, in the ordinary run of things.

But venture capital funds invest in a different kind of company - they invest in a particular type of startup, one that is much more likely to go to zero, but which has the potential, if it does succeed, to produce something very big. The enormous value created by the startups that really work is possible in a way that's not really true in many other places.

Silicon Valley investors don’t want a company that can churn out singles with every at-bat. They don’t want reliable profitability, or millionaire founders, or slow and steady growth. They want startups that are willing to risk going to zero for a reasonable chance of becoming huge, earth-shattering successes.

Venture capital is like rocket fuel. If you’re building a rocketship, you need it; if you’re not, it might make you explode.

In practice, aiming for venture-like returns often means making a number of counter-intuitive decisions when running your company.

First, you’ll decline deals that would make you a millionaire, as Mark Zuckerberg did:

[In 2006], Facebook was just two years old. It was a college site with roughly eight or nine million people on it. And, though it was making $30 million in revenue, it was not profitable. "And we received an acquisition offer from Yahoo for $1 billion," [Early Facebook investor Peter] Thiel said.

…At the time, Zuckerberg was 22 years old… Thiel said he and Breyer pointed out: "You own 25 percent. There's so much you could do with the money."

Thiel recalled Zuckerberg said, in a nutshell: "I don't know what I could do with the money. I'd just start another social networking site. I kind of like the one I already have."

This decision was Zuckerberg’s, to be sure, but there are plenty of times when a founder would want to sell and an investor wouldn’t — imagine a case in which a startup wants to sell for a respectable $50 million after one year of operations. An entire portfolio of $50 million exits wouldn’t make a VC firm very successful — so they’d want the founders to keep going — but the founders might make $20-30 million on the deal, enough to sustain them financially for life. If you’d quickly accept that offer, without question, being a venture-backed startup might not be for you.

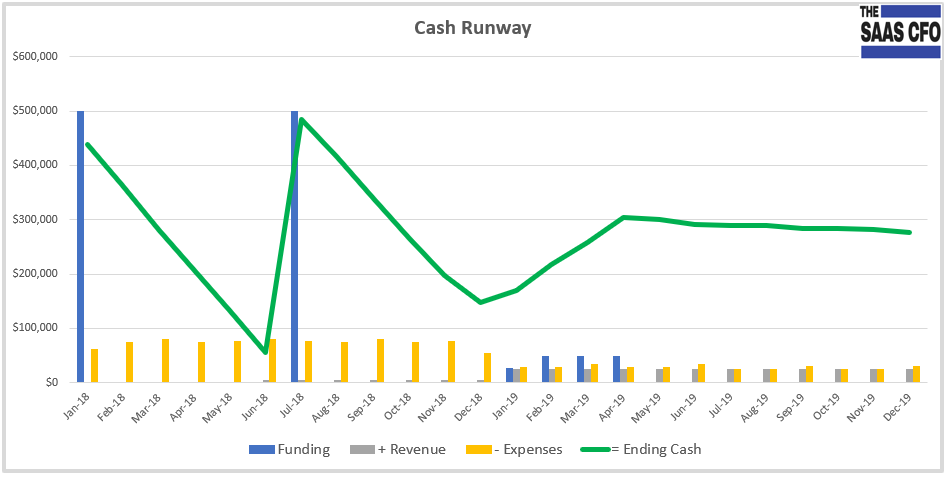

Second, you’ll delay making a sustainable profit. The goal of managing spend at a startup is not to make revenues greater than costs — it’s to set your “burn,” i.e., your monthly spend, to a level that will last you for about 18 months. At the end of those 18 months, you “run out of runway” (go bankrupt) unless you achieve enough to raise another round of capital and start the clock over again.

This strategy is considered the best way to move fast — just hire, buy, and invest beyond your means, and you’ll grow faster than you should. It also means that you’re constantly on a tightrope. Any deviation from the path, and you’ll plummet.

And third, you’ll be locked into your idea for a long time.

One of the best pieces of advice that I got while starting my own company came from a professor at Haas (the late Rob Chandra): don’t decide to go all-in on your company when you’re ready to commit the money, go all-in when you’re ready to commit your time.

A startup is a long journey. The median time from founding to IPO is about six years, and that’s just for successful companies. If you’re the founder, you’re locked into this venture for its life — from founding to either failure or success. Once you have venture capital behind you, walking away from an idea that isn’t working simply isn’t an option.

If your startup is going down, it’s your job to go down with the ship.

🌞 The alternative: a “lifestyle” business

If that model sounds great, great! But if you’d accept being a millionaire with stable cashflow and an escape hatch if something goes wrong, the Silicon Valley startup model might not be the best fit for your goals.

Although folks in Silicon Valley tend to use the “lifestyle” modifier in a derogatory way, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with choosing the option with greater flexibiltiy and lower expectations — especially if you can still achieve financial independence without ten years of grueling work as a traditional startup founder.

One of the most popular models for such a sustainable, flexible business comes from a Silcon Valley emigrant, Tim Ferriss. Tim wrote The Four Hour Workweek, and is a champion of “million-dollar, one person businesses.”

The basic goal of building such a business is to create an automated machine that produces reliable, consistent cashflow. To do so, you’ll violate many rules of building a Silicon Valley startup:

You’ll optimize for near-term cash, not long-term scale

You’ll outsource development and maintenance of the technical side

You will generally take yourself out of the process as much as possible

In Tim’s words,

Being busy is a form of laziness.

Doing less is the path of the productive.

That’s certainly not the Silicon Valley model, but it is a model. And now, whenever folks reach out to me to ask for my advice about starting a startup, I’ll direct them here.

Step One is deciding if you actually want to start a startup. Because starting a non-VC-backed company can still be rewarding, fun, and profitable. And you’d better know what you’re getting yourself into if you take the leap into the Silicon Valley pond.